|

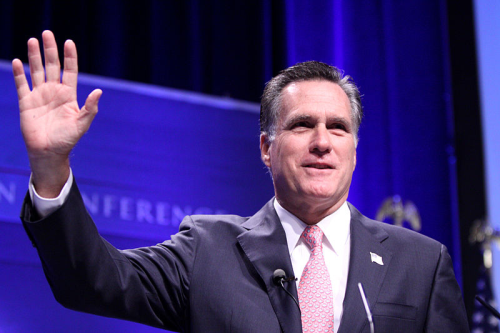

On Tuesday, George W. Bush offered his first endorsement of Mitt Romney, albeit offhandedly. After GW finished a speech on human rights in DC, the doors of an elevator were just about to close on him when he told a reporter, “I’m for Mitt Romney.” Romney got the formal backing of GW’s parents – George H.W. and Barbara – in March.

Mitt and Bush-the-younger exemplify how presidential aspirations sometimes run in the family. Mitt’s father, George Romney, had a storied political career, including a failed bid for the presidency. It has been said that Mitt grew up stumping in his father’s campaigns, and that he truly idolized his dad. Mitt himself has even said that he is his father’s son.

In some ways, their biographies are similar. Father and son both became successful business executives, earning millions, before committing themselves to running for office. George Romney headed Detroit’s American Motors Corporation from 1954 until 1962, during which time the company’s stock rose from $7 to $90 per share. He then became a two-term Republican Governor of Michigan, breaking a 14-year Democratic streak in that office, and eventually put in a bid for the presidency in 1968. Of course, Mitt’s claim to fame is that he spent many years at Bain Capital – whatever that is – before beginning his various forays into the political arena.

But their business records, and views on business, diverge on some points. George was described as a “a folk hero of the American auto industry,” and came to criticize what he saw as the twin evils of “big labor” in the Democratic Party and “big business” in the Republican Party. But Mitt eschewed the bailout of Detroit’s carmakers and, although he is no friend of unions, he seems to be a shining champion of big business. While head of AMC, George and other executives reduced their salaries by up to 35% and whenever he felt his own salary and bonus was too high in a given year, he gave the excess back to the company. As for Mitt, how long did we have to wait for his tax returns?

There may be differences, too, with respect to each man’s motivations and sense of self. At first blush it seems that George meant what he said and said what he meant; he entered politics guided by his own clear worldview. George, regarded by the GOP as self-righteous, was encouraged to run for president because of his views. He was a moderate Republican and he was favored as a counterpoint to the vexingly conservative Barry Goldwater. In 1964, George decided against running for president, partly because he promised the people of Michigan that he would stay on as their governor. When Goldwater became the Republican nominee, George did not hesitate to express his differences of opinion with the hyper-conservative (for example, George strongly disagreed with Goldwater’s antiquated disdain for the civil rights movement). During his gubernatorial campaign, if the press asked whether he was a Goldwater supporter, he would tell them, “You know darn well I’m not!”

Mitt, however, seems to adopt whichever views are best to win the race he happens to be in, including adopting the conservative GOP party line when it suits him. He draws constant criticism for being inauthentic, a notorious flip-flopper who changes his views at the drop of a dime. As pundits on both sides are quick to point, Mitt was a moderate as governor of Massachussetts (one term), but in the past year he had no qualms hiding those views under the couch so that he could puff out his chest as a “true conservative.” While pleasing most of the people most of the time may be a great skill for a business leader, when it comes to politics I really don’t see how Mitt supporters can abide by his lack of conviction on big issues – like abortion, for instance, or Obamacare (he may be aptly credited with inventing that one himself, in Massachusetts).

Mitt is not only a flip-flopper on his political views, but also on his political goals. After he left Bain in 1999, he considered the Senate or the governorship in either Utah or Massachusetts. One Romney aide offered this observation, “(Mitt) wanted to be governor. Whether it was governor of Massachusetts or Utah or Oklahoma, he didn’t much care. It was about winnability.”

Well, in any event, there is no question that he wants to be president. He is trying really hard, and spending an unfathomable amount of money. He has already gotten farther than his Dad did. Saying the right thing at the right time is a skill, I suppose. Although Mitt has had some gaffes, so far he has proved better at it than George, whose pursuit of the presidency ended quickly amid jeers at his claim that he was brainwashed by U.S. generals into supporting the Vietnam War.

Earlier this month, the NYTimes’ Paul Krugman wrote an op-ed piece called “Mitt’s Gray Areas,” in which he had this to say:

“… the contrast between George Romney and his son Mitt — a contrast both

in their business careers and in their willingness to come clean about

their financial affairs — dramatically illustrates how America has

changed…

What did George Romney do for a living? The answer was straightforward:

he ran an auto company, American Motors. And he ran it very well indeed:

at a time when the Big Three were still fixated on big cars and

ignoring the rising tide of imports, Romney shifted to a highly

successful focus on compacts that restored the company’s fortunes, not

to mention that it saved the jobs of many American workers.

It also made him personally rich. We know this because during his run

for president, he released not one, not two, but 12 years’ worth of tax

returns, explaining that any one year might just be a fluke. From those

returns we learn that in his best year, 1960, he made more than $660,000

— the equivalent, adjusted for inflation, of around $5 million today.

Those returns also reveal that he paid a lot of taxes — 36 percent of

his income in 1960, 37 percent over the whole period. This was in part

because, as one report at the time put it, he “seldom took advantage of

loopholes to escape his tax obligations.” But it was also because taxes

on the rich were much higher in the ’50s and ’60s than they are now. In

fact, once you include the indirect effects of taxes on corporate

profits, taxes on the very rich were about twice current levels.

Now fast-forward to Romney the Younger, who made even more money during

his business career at Bain Capital. Unlike his father, however, Mr.

Romney didn’t get rich by producing things people wanted to buy; he made

his fortune through financial engineering that seems in many cases to

have left workers worse off, and in some cases driven companies into

bankruptcy”

I think Krugman’s piece seems to emphasize that we are living in a very different America than did George Romney, in the 1960s. But the point I am stuck on the most is the change in taxation – George, who making a large yearly income ($5 million in his best year) was taxed at 36%. But some economists say the richest 1 % in the U.S. pay a top federal tax rate of only 29 percent,

according to Emmanuel Saez, an economist at the University of

California, Berkeley. Although the tax rate for their ordinary income is at 35% today, their capital gains and dividends are taxed at only a 15

percent rate. I am willing to suspend disbelief about a great many things, but I really don’t think there is a way to reduce, let alone just maintain, our national debt without raising taxes…