Written by Guest Contributor, C. Dillon

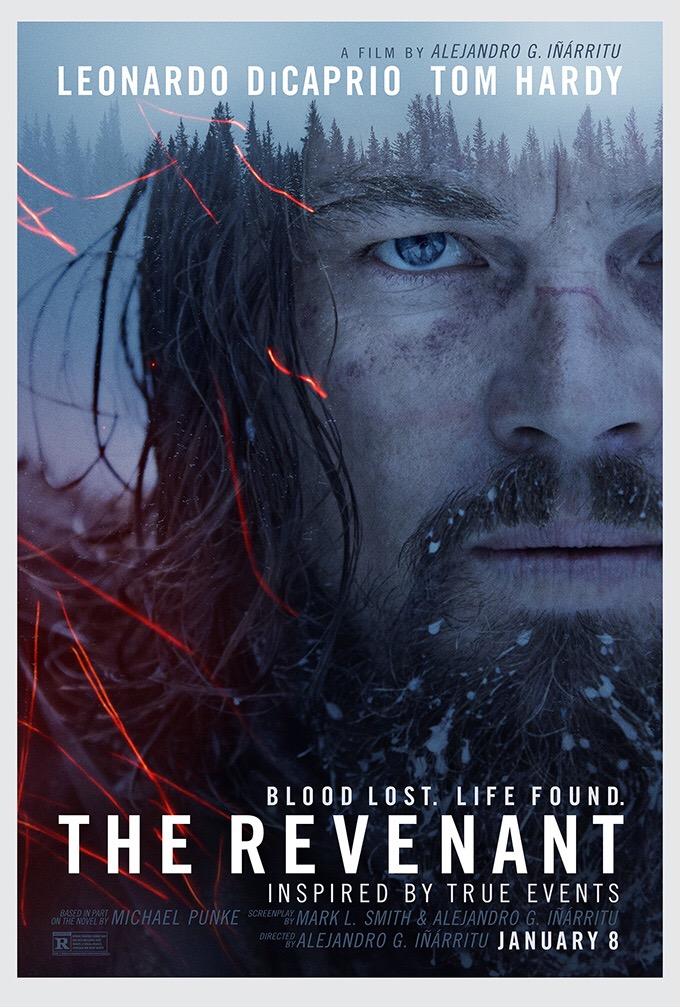

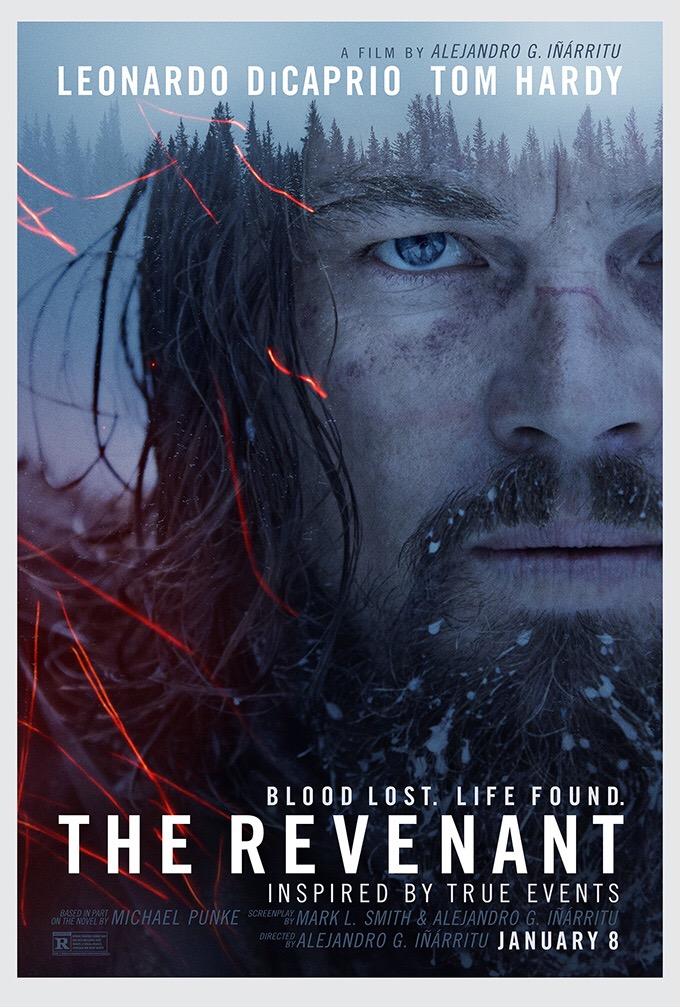

The Revenant is brilliant. Inspired by real events, The Revenant tells the story of Hugh Glass (Leonardo DiCaprio), a frontiersman and hunter working for a U.S. Government expedition to trap beaver along the northern reaches of the Missouri River in the 1820s.

Glass’ past is not deeply explored in the film, though it is shown that he was married to a Pawnee woman and lived with her (and their son, Hawk) until their village was raided and torched by (apparently) U.S. troops. Glass’ wife is killed in this raid, and young Hawk is badly burned. Glass’ mantra to his son while nursing him back to health – “as long as you can grab a breath, you fight” – echoes as the driving theme of the film.

Years later, Glass and teen-aged Hawk (Forrest Goodluck) are working under Captain Andrew Henry (Domhnall Gleeson), collecting beaver pelts in the frigid, mountainous forests lining the northern Missouri. The expedition is attacked by a group of Arikara warriors, forcing the survivors to flee down river. Concerned that the “Ree” will track and ambush their boat, Glass convinces Captain Henry to abandon the boat and continue on foot, trying to make their way hundreds of miles back to Fort Kiowa. Soon after, Glass is attacked and viciously mauled by a grizzly bear, suffering terrible wounds. The party tries to carry Glass with them, but it becomes apparent that they will not be able to get him through the snow-covered mountains in his condition. Captain Henry offers a substantial bonus to any volunteers who will stay with Glass until he succumbs to his wounds, and give him a proper burial. Hawk, his friend Jim Bridger (Will Poulter), and John Fitzgerald (Tom Hardy) agree to do so. Without getting too deep into spoiler territory, Glass is left for dead, and spends the rest of the movie trying to get back to Fort Kiowa to exact revenge on those who abandoned him.

It is a relatively simple story, but gorgeously told. Director Alejandro Iñárritu reteams with his Birdman cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki to paint a stark, violently beautiful portrait of the American frontier. Each shot is more beautiful than the last, whether it be leaves frozen in encasements of ice, or the open, snow-swept emptiness of a northern plain. In fact, I became so immersed in Lubezki’s realistic portrayal of Glass’ cold, wet world, I found myself shivering in the theater.

CGI is used sparingly, and in some cases with less than perfect results. One scene, however, makes heavy use of this technique to brutally effective ends. The attack on Glass by the grizzly is as visceral, immediate, and compellingly vicious as nearly anything ever put to film. Each swipe of rending claws, each gnash of crunching teeth is perfectly rendered, and makes this pivotal scene so realistic, it’s nearly unwatchable. The mass of the giant grizzly is a physical thing, felt by the audience as it tears Glass’ flesh to ribbons. It is a masterful scene of incredible violence, but even this feels somehow beautiful.

That the filmmakers paid incredible attention to detail is apparent in almost every shot. Specifically, Native Americans and First Tribes experts were consulted to ensure that the Arikara and Pawnee were accurately portrayed, down to the war paint on the horses. This pays off in spades, as there was never a moment in the film where an anachronistic gaffe pulled me out Glass’ environment.

Glass is a far cry from other characters DiCaprio has portrayed – often they are loquacious, easily charismatic types who have page upon page of sparkling dialogue to carry them. Not so in The Revenant, where Glass is naturally not prone to talking much, and spends a good deal of the movie unable to talk at all. This does not at all take away from his performance, however, he is as good here as he has been in anything. His face and eyes carry the burden of his pain, his loss, his lust for vengeance, where words would seemingly fail. It is a physical role, and an emotional one, and DiCaprio masters it.

He is surrounded by an equally adept supporting cast, led by Tom Hardy’s Fitzgerald. While he sometimes seems to be doing an impression of Tom Berenger’s Sergeant Barnes from Platoon (they are both hard men from Texas, after all), Hardy’s villain is both contemptible and, to a point, understandable. He knows what it means to be captured by the “Indians,” having lost a good chunk of his scalp in an earlier encounter. He accepts that this job, and this world, are brutal and unforgiving. He truly believes that Glass has no hope of survival, given their situation. All that said, however, he is not sympathetic, and the audience knows quite clearly that he is the bad guy in the story.

On a personal level, The Revenant – especially in the first 30 minutes or so – took me back to aspects of my own youth. As a young man assigned to the Army’s 2nd Ranger Battalion at Fort Lewis, Washington, I had spent significant time learning about “Roger’s Rangers,” a pre-Revolutionary War force that fought on the British side in the French and Indian War of the mid- 18th century. Modern Army Rangers trace their lineage directly from Roger’s Rangers, and include in their training “Roger’s Standing Orders,” a collection of things that every good Ranger – then and now – must to do be effective in combat. Watching Glass and his expedition patrol forested mountains, cold, wet, and under heavy burden, brought me straight back to my days doing the same (albeit 170 years later, and under very different circumstances). The Revenant is that kind of movie – it will hit you in places that you don’t expect, and bring you back to a time when you could be truly awed by a film.