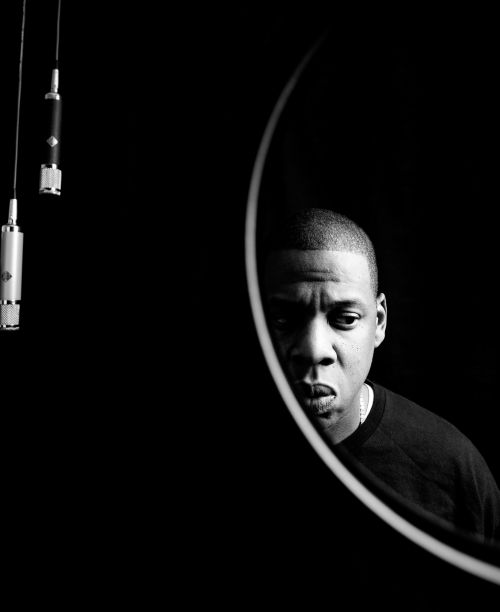

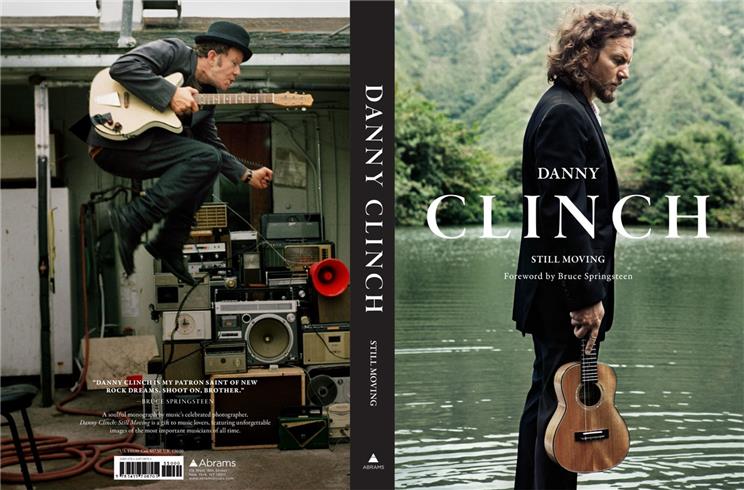

What exactly does it take to capture a rock G-d on camera, and can it be taught? Moments are fleeting, but when you have someone like Danny Clinch in your corner, those moments will live on, with the energy of the room fully intact. As a photographer and music-lover, Clinch is the go-to guy on the music scene, with work that spans album covers and publications like Vanity Fair, Spin, Rolling Stone, GQ, Esquire, and more. The New Jersey native began his career as an intern for famed Vanity Fair photographer, Annie Liebowitz, and though he was exposed to many genres at the time, Clinch found himself drawn to Liebowitz’s “early photos of John Lennon, the Rolling Stones on tour, and a specific one of Duane and Gregg Allman asleep in the back seat of the car.” Clinch “wanted to do it all,” but he just “naturally gravitated toward music.” And in case his photography resume of the Beastie Boys, Tupac Shakur, Johnny Cash and many more isn’t enough, Clinch has earned four Grammy nominations as a director. Plus, he has a book to his name, which is a curated collection of can’t-miss photographs. Read the interview below for a first-hand look inside the creative process of Danny Clinch.

You seem to have an ability to create trust and intimacy with people right away.

I just try to be myself, and I try to treat people as I would like to be treated. My world is relaxed. I’ve worked with other photographers whose world is not relaxed, so there’s tension and they use that to their advantage. I want you to say – “Wow, that was kind of easy, that didn’t feel like a photo shoot, it just felt like we were just hanging out.” I think it’s also important to be a collaborator, where people are interested in contributing to the photo shoot in one way or another. I think their involvement is important, and people won’t contribute if they don’t trust you.

What happens if you come across someone who doesn’t mesh with your style?

I feel them out, and I come with a set group of ideas. I am also very reactionary. For example, if we came into this room while we were sitting here, and maybe if the window’s open and then all of a sudden a cloud blows off the sun and a big streak of light comes through, I might say, “Oh! Go over there really quick! That light is beautiful.” Actually, one time I was photographing Bruce Springsteen for “The Rising” at a recording studio while he was mastering the record, and they said, “Well, you might get him every once in a while for five or ten minutes.” This was my first big shoot, and I thought, “Oh, great.” I was nervous, and he wasn’t really recording so there was a lot of down time. My assistant and I were hanging out in a parking lot. I already had some ideas, and he comes out and he says, “I got like five minutes, let’s do something really quick. What do you got?” I saw this rain puddle in the parking lot. I said, “Go on the other side of that rain puddle, and I’ll get a reflection.” So he goes over, and I got down and focused my camera, and all of a sudden the sun came out and it created this crazy shadow. So not only was it Bruce’s reflection in the puddle, but his shadow on top of it. This is pre-digital so I didn’t know what I got. I had to wait until I got my film back from the lab. I was like, “Oh my God.” I have learned to trust my instincts.

How do you feel about artists that don’t want the audience taking pictures during their concerts? Do you think iPhone cameras distract from the musical experience?

I couldn’t imagine being a performer looking down at someone while you’re singing these heartfelt lyrics and [seeing the audience] on their phone. It’s interesting as a photographer, because a lot of people only allow two songs for the photographer to shoot. Maybe someone should do the same for the audience. It’s only fair. People are missing the experience.

You have said Keith Richards was the classic subject to photograph. What makes a subject so interesting?

Everyone is different. Some people are great collaborators and know how to be in front of the camera, and some people have to learn it. Others will never learn it. They might say, “This is me, I’m going to sit here. You make the photo as best you can,” and it’s up to you to direct them in a certain way or stand them somewhere interesting. Then you have people like Bruce Springsteen or Keith Richards, for example. Keith is the great example, because I had never photographed him and he was on my bucket list. When I got a chance to photograph him, I took a polaroid, and when I looked at it, I had an epiphany and thought, “These weren’t great photographs, this is a great model!” I mean, this guy is unbelievable! He’d just sit there, and just came off so rock ‘n’ roll. You can’t take a bad picture of this guy. Of course, he was pretty cool. He wasn’t super-friendly, but he was immediately into the vibe.

Is it easier with someone who is experienced?

Yeah, and somebody like Bruce Springsteen, who has been photographed so many times, knows how to project, at least to himself. He’s like, “I remember I did this in this photo, and when I got it back I really liked it.” If you’re photographed every single day, you know “this is the better side of my face; this is not.” For instance, this Gregg Allman photo right here which is staring me in the face. It’s a great captured moment, but in my mind, being a photographer who has been there a million times, did he know the photographer was there, and he threw his leg up there and thought, “I’m going to give this to you, go ahead and get it.” [Laughs]

When I think of someone like Keith Richards, he’s such a defined look. Does the look play into it too?

Oh, of course. It’s what people are wearing, their style of dress, their body language, and I’m a big fan of the moment when they’re not quite ready. If I’m having trouble with someone– if they’re a guitar player and I put a guitar in their hands, they all of a sudden forget, their shoulders relax, they start tuning the guitar, it’s a real moment. If you look at some of the photos in this room, for instance, like that Jim Morrison photo by Joel Bronson, it’s very direct, and it’s in a studio. He knows this is not a captured moment; this is a direct portrait. And there’s a lot a lot of value in that too, and I love those moments. My preference is the more captured moment. Also, something that I say in my book, “Still Moving,” is that I don’t always think that a portrait has to be where you can see someone’s face with direct eye contact. There’s a Bob Dylan photo in my book also where he’s looking out a window and I think it’s a beautiful portrait, and it speaks volumes. You don’t see his face but you look at it and you’re like, “That’s Bob Dylan.”