Steve Gadd’s musical story starts early. Born in Rochester, N.Y., Gadd was given drumsticks by his uncle at age three. By seven, he received a drum set from his grandfather, which led to his first formal lessons. At 11, his parents began bringing him to local jazz clubs to see legendary performers such as trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, who let Gadd sit in during a Sunday matinee. It was during that time that he first met jazz great Chuck Mangione, whose quintet he later joined along with then unknown pianist Chick Corea (Corea would later recruit Gadd for his own band). Mangione recalled his early years with Gadd, saying, “Steve was amazing at the age of eight. He was fundamentally sound in every area of the drums.”

Shortly after college, Gadd enlisted in the U.S. Army and played in their big band for the next three years before finally returning to the New York studio scene, which ultimately landed him two of his most iconic performances in history: Paul Simon’s “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover” and Steely Dan’s “Aja.” When Gadd was commissioned for Steely Dan’s title track, it was widely rumored that despite numerous takes from many other drummers, Walter Becker and Donald Fagen still hadn’t found a drummer that fit their vision for the song. Gadd famously performed his part in one take. According to Becker, “Gadd’s part was not written. [They] discussed the tune a little bit and by virtue of his musicianship he just knew what to do.” Fagen agreed, explaining that Gadd was one of the rare players “who was familiar with R&B’s backbeat and could negotiate jazz harmony with ease.” Paul Simon similarly reflects on his work with Gadd, calling him “the greatest drummer of his generation.” Simon and Gadd’s work together now spans decades, along with James Taylor, Eric Clapton, and many others.

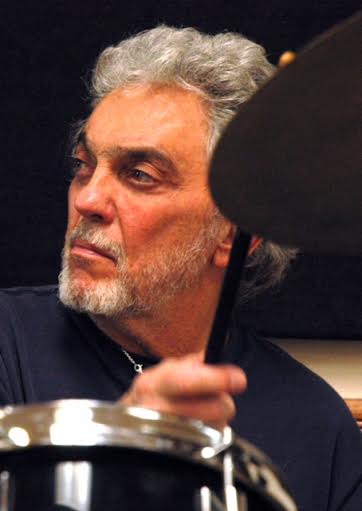

The major takeaway from talking to Steve Gadd isn’t the technical elements of his talent and his impressive resume. It’s his humility. He’s had some of the most high-level gigs in history, and he does not take it for granted. He looks at every performance as an opportunity, and he’s simply grateful for the chance to do what he loves. When I asked Grammy-winning producer Peter Asher about working with Gadd, he eloquently explained the importance of his contribution, saying:

Throughout the history of jazz and rock and roll there have been a few great drummers whose touch, whose ideas, whose groove and whose tone were wholly distinctive and capable of changing the direction of a specific track or even music as a whole. The influence that the past masters (people like Gene Krupa or Max Roach or Kenny Clarke) had on the music of their time is matched by very few players today – and preeminent among those players is Steve Gadd. He contributes to the very essence of the songs and tracks on which he plays. Elegant, distinctive, witty, inventive – and yet somehow irresistibly funky at the same time. He plays like a gentleman- but a gentleman with a deep and dark soul.”

Read my interview with Steve Gadd below.

I’m always interested in the nature-vs.-nurture side of talent and creativity. I know your uncle bought you drumsticks at the age of three. Had he not provided that encouragement, do you think you would have gone down the same path?

I don’t think so. They saw interest, which guided me. My uncle gave me those drumsticks before we had television, and my grandmother used to take me for lessons. I lived with my parents, my grandparents, and my father’s brother. My grandparents and my uncle had horses, so I’d go to the barn and hang out with the horses. After they were bedded down, my uncle and I would put on records and the whole family would listen. We’d put on John Phillip Sousa marches and play on little round pieces of wood. It was a family affair.

Do you think they knew almost immediately, though, that you had an innate pull toward drumming?

Yeah, my uncle gave me sticks because I was banging with knives and forks. He saw that I had that inclination. He was a drummer in high school and he played in a parade with veterans. He had this red parade drum that I’ll never forget, and that was the first drum I saw. He was playing it in the parade. They just saw that I had an interest, and they nurtured it.

You’re a session drummer and a live, touring musician. Do you have a preference?

No, I like both. If the musicians are good and the music is good, they’re both enjoyable. It can get a little wearying to be away from family on the road, but musically I am inspired by both.

Your intro to “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover” is iconic. Are there any drum parts that were equally influential to you?

Not drum parts, per se, but there were drummers – Buddy Rich, the Dorsey band, Gene Krupa with his band, Benny Goodman, and hearing a recording of Louie Bellson doing “Skin Deep” with double bass drums. Those were iconic drummers. I was influenced by them and by what they did. There wasn’t a part that they played, but it was everything they did.

The intro to “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover” has a marching style to it. I know you spent about three years in the military. Did that play a role?

Not the military, but I played in drum corps as a kid and we had a great drum line. They were my good friends, and we were pretty serious about writing our own parts and teaching the guys to play the parts. So I’m sure that had some kind of influence.

I’ve read a lot about your performance on Steely Dan’s “Aja.” As I understand it, you weren’t aware that Steely Dan already had other drummers record drum parts but weren’t happy with their performances.

No, I knew that. I think I’d heard that. I was doing a lot of recording back then, so I got the call. The band was there, and we did it live. They were well-rehearsed because they’d played it with different drummers. I didn’t hear what they did with other drummers, and I’m sure whatever they did was good. It was just a matter of whatever was done was not exactly what Walter and Donald were looking for, and somehow they were able to communicate it to me and we just went for it. So I was aware that other drummers were called to do it, but you never know which one they’re going to use. I didn’t know at the end of what I did whether they were going to end up using it or using something that someone else did. You never know. You just try to do your best.

Did you have a feeling after, like, “Man, that one worked.” Could you feel the energy when it was complete?

I felt like they liked what happened. It wasn’t as if I was trying to go in there and do my set. I was going in there to try and understand what it was they were going for and to try to give them that. You could feel the positive energy at the end of that session.

I’m sure you’ve had experiences where you feel like the energy in the room is not conducive to optimizing creativity. How do you handle that?

You just give whatever it is you give to try and make it happen. Whatever knowledge and experience that I have, I would put all my energy into just getting past that. A lot of times there’s just a miscommunication, so if you can help the line of communication or if you can help someone understand, it takes it to another level. Hopefully that would help, but there’s no guarantee. You just do the best you can.

I read an interview with Steely Dan that you’re playing worked so well because of your jazz background. Do you think it’s necessary for up-and-coming drummers to master all genres?

The things that I’ve mastered were things that I’ve loved, so I’ve just followed my heart. I think that if they hear jazz and they like it, then it’s worth pursuing, not for any other reason than to enjoy playing that kind of music with people who play that way. That doesn’t mean you’re going to get called to do that, but there’s a possibility that you’re going to have a good time with good players playing good music, and that’s the inspiration.

Do you think it’s an advantage that you learned jazz first, since it’s a more complex genre?

It was good for me. I don’t think that there’s any one way that works for anyone. I think it can work different ways for different people. There’s a lot of jazz drummers back in the day that weren’t inspired by groove or pop kind of music. At a certain point, I went to New York and I heard some guys play very simply and the groove was deep. You’d think it’s a simple, less technical approach, but it’s not. It’s not an easy thing to do. It’s just as challenging as playing very busy, but in another way. The drummer I heard do it the first time was Rick Marotta, and that’s what inspired me. To play less notes and make it feel the best it could feel, and to record where you start with the minimal amount to make it feel musical and then add as you go, it gives you somewhere to go. If you start at technical level 1 and volume level 10. you’ve got nowhere to go.

You’ve talked a lot about your desire to challenge yourself.

If I’m sitting down practicing, I’m always trying to look for new things. Yeah, I do that. When I was in the studios a lot, whatever calls came in I would take, no matter what they were. I’d just go in and do my best. Now, the studio scene isn’t the same anymore. It’s a lot different. If I was in New York and I was in a position to be in the studio, I would take whatever came in and try to do the best I could. If it was something I couldn’t do or I didn’t do as well as I wanted, I’d probably just go home and try and do it better.

When you say the studio scene is different, do you mean because of how the music industry has changed, or are you just referring to the fact that you’re no longer in New York?

Both. First of all, there’s not as much recording as there used to be when I was living in New York. Back in those days, there were advertisements, record gigs, and it was from morning until night. Since then, a lot of the studios have closed down, and there’s MIDI instruments where one guy can program everything. It’s a whole different ballgame. It’s not better or worse now, it’s just different. I still get some recording and I do my own stuff, but it’s not like when I was living in New York getting calls tonight to show up tomorrow at 10:00. It’s not that way now.

It sounds like you’re not necessarily upset about it, you’re just saying it’s different.

I’m not upset, I’m very grateful for the music that I’ve had the opportunity to play. I feel really lucky. I play with great musicians either in my own band or if I’m out with James Taylor, Eric Clapton, David Sanborn with Bob James, or Will Lee. I play with some great players, and I love their music, so I feel pretty cool. I like spending time with my wife and seeing the kids when I can. It’s good.

You’ve talked a lot about self-evaluating, and I know you’ve said that when you’ve listened to your playback in the studio, it’s eye opening. When you’re playing live, can you get that same feeling in the moment of what works?

It’s a different thing. It’s not necessarily based on what you’re gonna hear back but on how much higher the person you’re working with is playing and how the audience is responding. There’s different ways to gauge it. And hopefully if you get a chance to hear it back, it will be something that you’ll like.

When you work with people like Eric Clapton or James Taylor, do you feel more creative freedom because you have worked with them in the past?

You sort of know what the music needs and you just try to get it to a certain level every night. The person you’re working with should get what they need. The bottom line is when you’re working with Eric Clapton, the arena’s going to be full. It’s about doing what you have to do for the music of the artist that hired you. You creatively figure that out in rehearsals. Then it’s just a matter of trying to get yourself ready to do it every night as if you were doing it for the first time.

Is it difficult to sustain that energy level when you’re performing songs that you‘re so familiar with?

Not if you’re clear about the job. It’s difficult if you’re thinking that you’re not doing as much as you can do creatively. You’ve got to just get your head around what you’re supposed to do. The performance takes a lot of energy. You’ve got to deal with monitors, different kind of halls every night, etc. There are hurdles to jump over when you’re on the road, even if you’re playing the same stuff every night.

You’ve discussed how you loved working with Chick Corea because the drum parts were not written. Is that something you prefer?

What I meant was the music was all written out, but I was reading off the piano score, so it was open for interpretation. I had music in front of me that was guiding me and his writing is beautiful, so it was just clear to me what I thought it needed. It was challenging because the writing was very high-level, and we recorded it live. It encompassed a lot of different areas of music that you work your whole lifetime to be able to achieve. You don’t always get in those situations where you’re able to apply everything, but that was one where I could pretty much apply it all – I could apply jazz, funk, reading music, playing in an orchestra – all of those things played a part in how I interpreted what I did for that music.

I would also imagine when you record live it creates a different energy in the room.

Yeah, all those situations are different when you record live. It’s another kind of pressure that you have to deal with. You have to work your mind to stay relaxed and remember that all it’s got to do is really feel good and everything else will fall into place. I don’t get too personal and try to get too slick with what I’m doing. I try to just be part of the process and do things for everyone else.

Tell me about your upcoming album.

I just finished our second album with the Steve Gadd Band, and we’re still mixing it. We haven’t decided on the title yet. Our first LP is called Gadditude, and it’s with the guys that I play with in James Taylor’s band: Larry Goldings (keys), Michael Landau (guitar), Jimmy Johnson (bass), Walt Fowler (trumpet). I like the music, and there’s a lot of original stuff. These guys are great players and they’re great friends and we love hanging together. It’s a lot of fun. I’ve also been doing some projects with Edie Brickell.

I love Edie!

Edie writes all the songs and I produce them. She came up with the name of the band, The Gaddabouts, because she doesn’t like to put herself in front, but it’s all her music that we played and worked out in the studio. There are two albums out, and we’re just about ready to release the third. I’m really proud of that music and being involved with producing with people that I really love.

Is it more enjoyable to lead your own project?

Whatever music I play is special to me, regardless of whether it’s my thing. I wouldn’t approach working for someone else any less diligently than I would approach doing my own thing. The thing that’s nice about doing my band is that I can make more decisions musically. It’s a growing situation for me. I’m learning something that I never did before and getting to spend more time in the studio, so I like that.